(english version below)

Hidden home

Betritt man die Ausstellungshalle, befindet man sich in einem riesigen Wohnraum, jedenfalls auf den ersten Blick. Ein Doppelbett in der Mitte, ein Bügelbrett, drei monumentale Bilder an der Rückwand, wie Fenster, zwei kleinere an einer Seitenwand – fast alles rot-weiß, zersplittert, gebrochen, fragmentiert. Und eine blonde Perücke auf einem Sockel. Scheinbar jedenfalls. Doch dazu später.

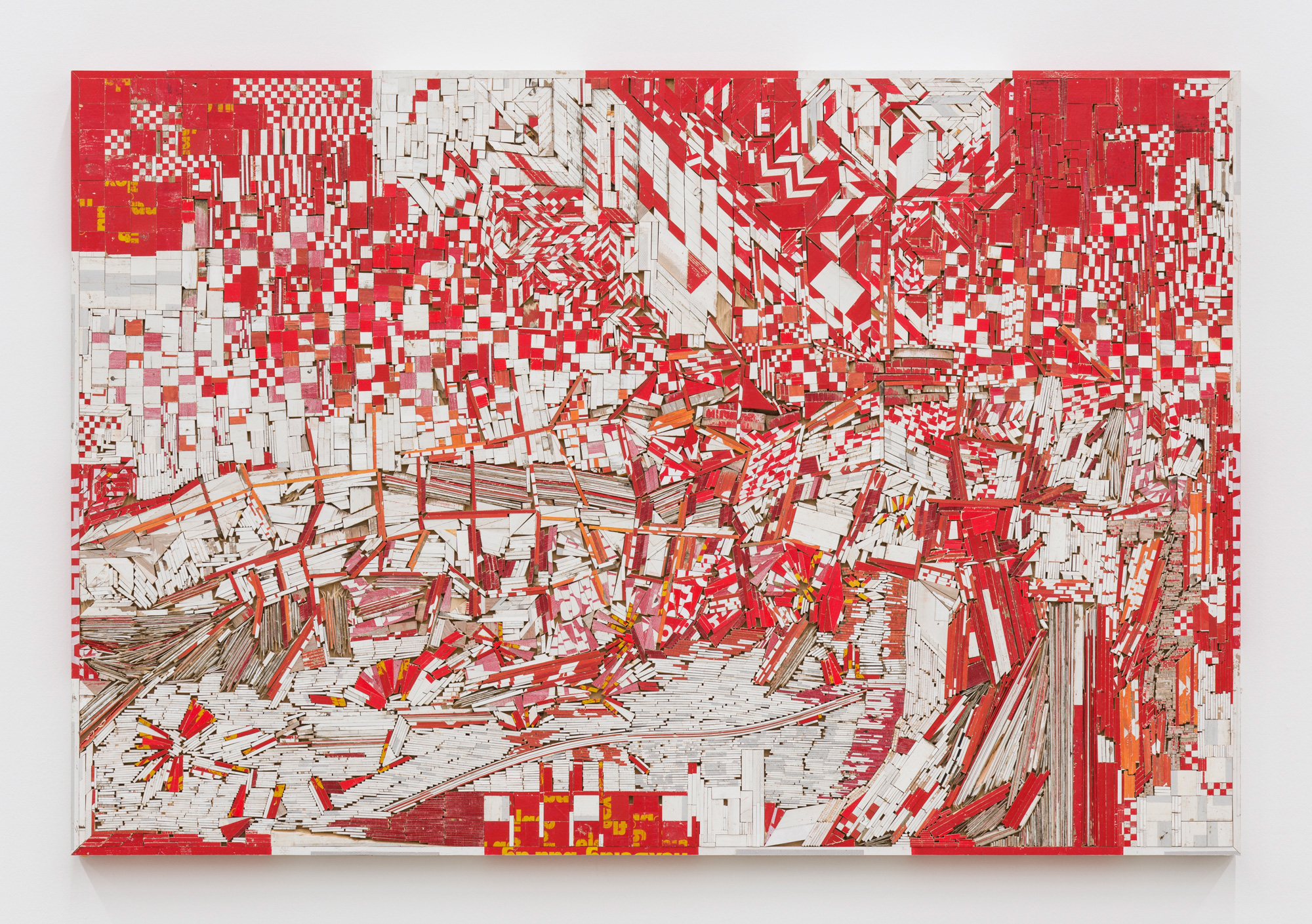

Hannah Parr, an der Südküste Englands aufgewachsen, lebt und arbeitet in Zürich. Ihre mosaikartigen Arbeiten stellt sie mit, in der Schweiz gebräuchlichen, rot-weiß gestreiften Baustellen-Absperrlatten her bzw. mit Teilen derselben. Auch die drei monumentalen rot-weißen Mosaike an der Rückwand der Ausstellungshalle bestehen aus solchen Fragmenten. Die zunächst rein abstrakt erscheinenden Mosaike zeigen drei radikal abstrahierte Landschaften – links eine fiktionale, in der Mitte eine erinnerte, rechts eine reale.

Das fiktionale Hochformat auf der linken Seite zeigt abstrahiert und fragmentiert ein Interieur mit Tisch, Vase, einer drapierten Decke und Blick aus einem Fenster auf eine Landschaft mit Feldern. Das Querformat in der Mitte bildet eine schroff abfallende Klippe ab, Meer und Himmel, eine erinnerte Kindheitslandschaft der Künstlerin. Das Hochformat rechts daneben ein steil aufragendes wirkliches Alpenmassiv, über dessen Höhengrad sich eine Wolke schiebt. Diese Abbildungen sind so abstrahiert, dass immer auch andere Lesarten möglich sind. So könnte die drapierte Decke des Interieurs auch Felder aus der Vogelperspektive darstellen. Fast immer bestehen die Arbeiten aufgrund der vielen Holzteile aus Schichtungen, ebenso wie die südenglischen Klippen aus den Kindheitserinnerungen der Künstlerin oder die Schweizer Berge, von denen Parr bei ihrer Arbeit täglich umgeben ist.

In der Mitte des Raums steht ein gusseisernes Bett, auf dessen Rost ebenfalls Lattenteile montiert sind, so dass auch dieses von einem Mosaik bedeckt wird. Nicht weit vom Bett ein Bügelbrett, ebenfalls mit Mosaik. Auf einem Sockel, wie auf einem Beistelltisch, ein rundes Akkuladegerät, an dem, wie bei einer Perücke, blonde Kunsthaare befestigt sind. Das Ladekabel mit Stecker hängt vom Sockel frei herab in der Luft. Wie schon das Bett und das Bügelbrett verweisen die Haare auf menschliche Gegenwart. Das Bügelbrett könnte auf Arbeit, Ordnung und Kontrolle verweisen, das Bett hingegen auf Träume, „Unordnung“ und Nacht. Auch dies jedoch nicht eindeutig, denn die Künstlerin erklärt, sie könne im Bett nicht nur träumen, sondern vor allem „klar denken“.

In eine Seitenwand der Halle ist ein Feuernotfallschrank aus Metall eingelassen. Kein reiner Wohnraum also, wie man auf den ersten Blick vermuten könnte, sondern auch industriell oder gewerblich anmutende Elemente. Hinter den Türen des Notfallschrankes aber weder Schlauch noch Feuerlöscher, sondern ein Föhn und Holzscheite, Utensilien also, ein Feuer anzufachen, nicht zu löschen. Ein Feuerlöschschrank als Kamin und Feuerstelle. Heimelig und bedrohlich zugleich.

Was ist das für eine konstruierte und dekonstruierte, was für eine heimelige und doch auch fremde, für eine gewohnte, aber auch irritierende Welt? Was ist das für ein hidden home? Schon der Ausstellungstitel deutet auf Ambivalenz und Contradictiones in Adiecto hin, auf Widersprüche in sich. Ein Zuhause zwar, aber ein verstecktes. Nah und fern zugleich. Zugänglich und versperrt.

Das Material, Absperrlatten, kommt sonst nur in der Öffentlichkeit zum Einsatz und im Außenbereich. Die Latten dienen der Abgrenzung, aber auch der Warnung vor Gefahr. Parr versetzt dieses Material von der Straße ins Private. Dieses, im Wortsinn, sperrige Material dient Parr zur Konstruktion einer Heimstatt, die Archetypisches und Unbekanntes verbindet. Gleichzeitig konstruiert und dekonstruiert, zeigt uns die Künstlerin ein Heim, das uns einerseits wie gewohnt und gewöhnlich umgibt, das aber andererseits auch auf ein Heim in uns selbst verweist, oder eine Sehnsucht danach, und auf ein Heim jenseits unserer Wirklichkeit. Auf eine Terra incognita. Einen Traum? Das zentral positionierte Bett könnte darauf hindeuten. Oder eine Utopie? Die großen Mosaike scheinen den Raum zu einer unbekannten Außenwelt zu öffnen – allerdings mit Absperrlatten! Contradictio in Adiecto.

Terra incognita nannten die Europäer im 15. und 16. Jahrhundert die noch nicht von ihnen „entdeckten“ oder kartographierten Gebiete. Man begab sich auf die Suche nach „neuen Welten“. Im 19. Jahrhundert kam die Erkundung des – als „Seele“ bezeichneten – „inneren“ Ichs hinzu, Psychoanalyse genannt. Seelenzergliederung. Ähnlich dieser Seelenreise ins Unbekannte, „zeichnet“ Hannah Parr mit tausenden von Holzstückchen ihre eigene Suche auf. Dabei kartographiert sie die Außenwelt und ihr Inneres.

Die Herstellung der großen Holzmosaike ist ein langsamer und lange andauernder Prozess, für Parr eine Reise ins Unbekannte, aber auch ein rebellischer Akt gegen die allgegenwärtige Beschleunigung. Ausgangspunkt dabei mögen vertraute Bilder sein, der Weg aber und das Ziel sind ihr nicht bekannt. Während des Arbeitsprozesses ist die Künstlerin äußerst fokussiert und ganz bei sich. Insofern gleicht die künstlerische Arbeit ihrerseits einem Zuhause, einem Ort, an dem man zu sich selbst findet und eins mit sich wird – Identität gewinnt. Dies bleibt allerdings ein jederzeit widersprüchlicher Vorgang. Mit Fragmenten gegen die Fragmentierung. Eins mit sich, unter tausenden von Teilen, die zusammen wiederum ein unbekannt-bekanntes Ganzes geben, eine Terra incognita und ein Vertrautes. Ein Heim. Verdeckt. Versteckt. Immer innen und außen zugleich. Ganz wie wir selbst.

Hidden home

Entering the exhibition hall, one finds oneself in a huge living space, at least at first sight. A double bed in the middle, an ironing board, three monumental mosaics on the back wall, like windows, two smaller ones on a side wall – almost everything red and white, fragmented, broken, split. And a blond wig on a plinth. Seemingly, anyway. But more on that later.

Hannah Parr, who grew up on the south coast of England, lives and works in Zurich. She creates her mosaic-like works from red and white barrier slats that are commonly used in Swiss construction sites. The three monumental red-and-white mosaics on the back wall of the exhibition hall also consist of these slats. The mosaics, which at first seem purely abstract, can be seen as radically abstracted landscapes – a fictional one on the left, a remembered one in the middle, and a real one on the right.

The left mosaic suggests an abstract and fragmented interior with a table, a vase, a draped ceiling, and a window view of a landscape with fields; the middle one a rugged cliff, sea and sky, a remembered childhood landscape of the artist; and the right one a steeply rising alpine massif, over whose ridge a cloud floats. Almost always, the works consist of layers due to the many wooden pieces, just like the southern English cliffs from the artist’s childhood or the Swiss mountains that Parr is surrounded by in her atelier.

At the center of the space is a metal bed whose frame is covered with a mosaic. Not far from the bed is an ironing board, also mosaicked. On a plinth, almost like a side table, sits a round battery charger, to which artificial blonde hair is attached, like a wig. A charging cable with a plug hangs freely from the plinth. Like the bed and the ironing board, the hair refers to human presence. The ironing board signifies work, order and control, while the bed refers to dreams, disorder and the night. This too, however, is not unambiguous, as the artist explains that she can not only dream in bed but above all “think clearly”.

A metal emergency cabinet is embedded in a sidewall of the hall, which does not depict a pure living space, as one might assume at first glance, but also incorporates industrial or commercial-looking elements. However, behind the doors of the emergency cabinet, we find neither hose nor fire extinguisher, but a hairdryer and wood chocks, utensils to start a fire, not to extinguish it. A fire extinguisher cabinet as a fireplace. Homey and threatening at the same time.

What kind of a constructed yet deconstructed, homey yet strange, familiar yet irritating world is this? What sort of hidden home is it? The title of the exhibition points to contradictions: a home indeed, but a hidden one. Near and far at the same time. Accessible yet blocked.

Barrier slats are typically used in public spaces and outdoors. The slats serve to delimit but also to warn of danger. Parr transfers this material from the street to the private sphere. This barrier material serves Parr to construct a home that combines the archetypal and the unfamiliar. Simultaneously constructing and deconstructing, the artist shows us a home that, on the one hand, surrounds us as usual, but on the other refers to a home within ourselves, or at least a longing for it, and to a home beyond our known reality, to a terra incognita. A dream? The centrally positioned bed could indicate that. Or a utopia? The large mosaics seem to open the space to an unknown outside world, but one delimited by barrier slats! Contradictio in Adiecto.

Terra incognita is what 15th and 16th century Europeans called places they had not yet “discovered” or mapped. They went in search of “new worlds.” In the 19th century, the exploration of the inner self, or the “mind”, began later to become known as psychoanalysis. Similar to this voyage of discovery into the subconscious, Hannah Parr “draws” her own search using thousands of pieces of wood. In doing so, she maps the outside world and her inner self.

The production of large wooden mosaics is a slow and painstaking process, for Parr a journey into the unknown, but also a rebellious act against an omnipresent sense of acceleration. The starting point may be familiar images, but the path and the destination are unknown to her. During the working process, the artist is extremely focused and completely with herself. In this respect, the artistic work itself resembles a home, a place where one finds oneself and becomes one with oneself – gains identity. This, however, remains a process that is at all times contradictory. With fragments, but against fragmentation. One with oneself, among thousands of parts, which together in turn create an unknown-known whole: a terra incognita and a familiar one. A home. Concealed. Hidden. Always inside and outside at the same time. Just like ourselves.