(english version below)

Werther to go

In seiner ersten Ausstellung bei SEXAUER unter dem Titel Bastard Club zeigte Alexander Iskin im Jahr 2014 Ölgemälde verstörend-komischer Mischwesen in apokalyptischen Landschaften. Zwei Jahre später mischte Iskin nicht mehr nur Wesen, sondern Wirklichkeiten. In seiner Ausstellung Reality Express untersuchte er malerisch und installativ, wie sich analoge und virtuelle Realität gegenseitig durchdringen. Der Interrealismus war geboren. Seitdem entwickelt und erkundet Iskin den Interrealismus als künstlerische Praxis, Ästhetik und Medienkritik. 2020 widmete ihm das Mönchehaus Museum seine erste institutionelle Einzelausstellung. Damit war auch der Interrealismus im Museum angekommen.

Nachdem Iskin die Interrealität ein halbes Jahrzehnt malerisch, installativ, filmisch und performativ erkundet hat, legt er nun einen interrealistischen Roman vor, der 2022 erscheinen wird. Werther to go. Dieser Text bildet buchstäblich die Grundlage für die gleichnamige Ausstellung. Auf den Boden der Ausstellungshalle hat Iskin hunderte gedruckte Romanzitate auf weißen Grund gesetzt. Die Halle wird zum White Cube, zum idealen und hermetischen Raum. Bewegen sich die BesucherInnen in diesem, nehmen sie lesend oder unbewusst die Textfragmente wahr.

In seinem Roman Werther to go beschreibt Iskin die Auswirkungen der Virtualität und des Digitalen auf die Generation Z, die Kohorte der Post-Millennials, die keine Welt ohne Internet mehr kennen. Durch digitale Manipulationen sind die Jugendlichen einer extremen Kommerzialisierung und auch anderen Manipulationen ausgesetzt. Während die Romanfragmente den Boden bedecken, hängen an den Wänden gemalte und teils dekonstruierte Portraits der fiktiven Romanfiguren. So begegnen wir im Inneren des Würfels der künstlerischen Transformation einer Lebenswelt der Generation Z.

In dem der Ausstellung zu Grunde liegenden Text von Iskin verliebt sich ein, bei einem Software-Unternehmen angestellter, Berufshacker in ein junges Mädchen, das er ausschließlich aus einem sozialen Netzwerk kennt. Das eher naturverbundene und zurückhaltende Mädchen ist neu in der Großstadt. Es hat Probleme mit seinen als cool geltenden MitschülerInnen, sucht Hilfe auf dem Internetportal gutefrage.net und liest Goethes Briefroman Die Leiden des jungen Werther. Über eine künstliche Intelligenz, welche die Sprache Werthers imitiert, versucht der Berufshacker inkognito, das Mädchen auf der Plattform zu manipulieren. Dieses erweist sich jedoch als widerständig. Am Ende versucht der Hacker, die Protagonistin in seine Gewalt zu bringen, in der virtuellen wie auch der wirklichen Welt.

Natürlich ist es kein Zufall, dass die Protagonistin in Iskins Roman Die Leiden des jungen Werther liest. Der Werther wurde seinerzeit als Gegenentwurf zu einer als kalt und rationalistisch empfundenen Aufklärung verstanden. Für die Protagonistin in Werther to go ist der Werther auch ein emotionaler Gegenentwurf zur Kälte des Digitalen: Gefühl statt Kommerzialisierung, Wahrhaftigkeit statt Simulation, Natur statt McDonalds. Andererseits – und das ist das Paradox – beeinflusste Goethes Werther die Jugend damals ähnlich stark wie heute die digitalen Medien. Nach der Veröffentlichung des Romans im Jahr 1774 soll es zu suizidalen Nachahmungen gekommen sein, heute bekannt als Werther-Effekt. Dem nicht unähnlich, verabreden und diskutieren Jugendliche heute, über zweihundert Jahre später, ihren Freitod in Suizidforen.

Im Unterschied zur Werther-Zeit werden die Heranwachsenden heute nicht mehr durch die Lektüre eines exzeptionellen Buches beeinflusst, sondern verbringen einen Teil ihres Lebens in einer Parallelwelt der digitalen Realität. Nicht wenige sind süchtig nach dieser. Nur selten sind sie zur Gänze in der „wirklichen“ Welt, vielmehr fast immer mit mindestens einem Auge in der virtuellen. Gefangen in der Interreality. Scheinbar freiwillig. Tatsächlich manipuliert.

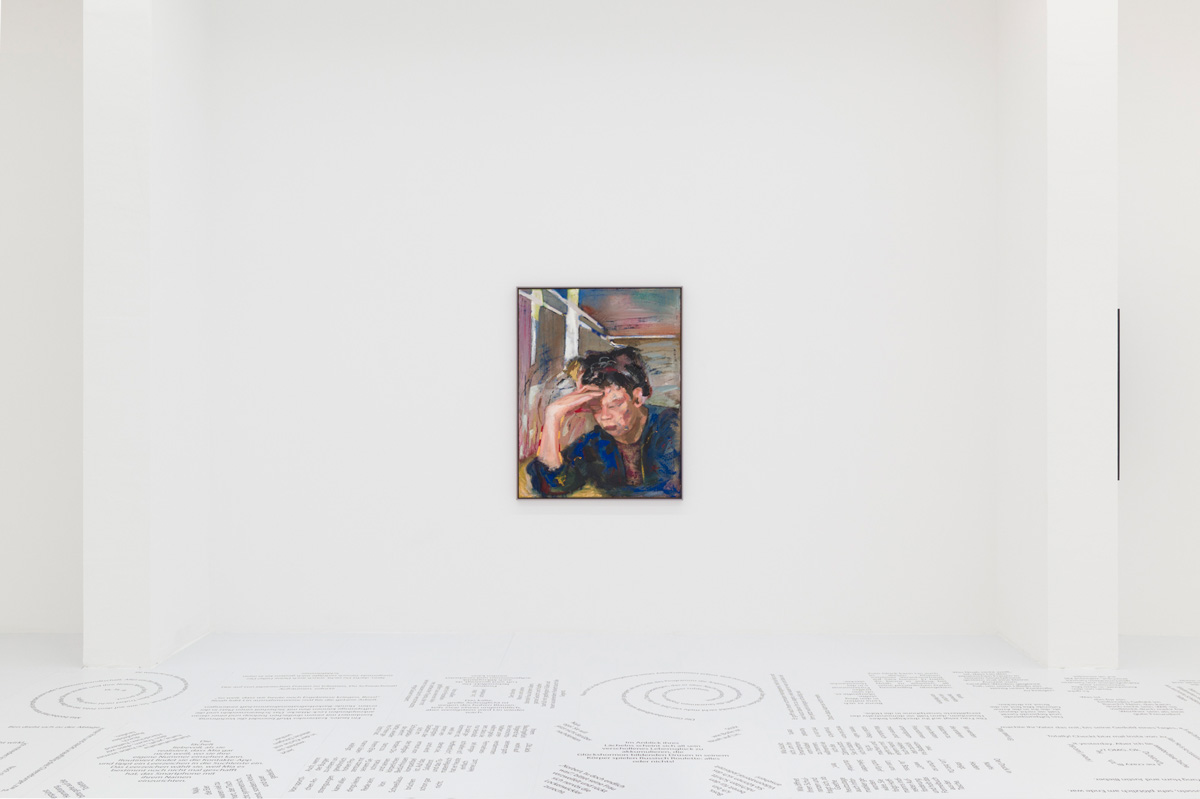

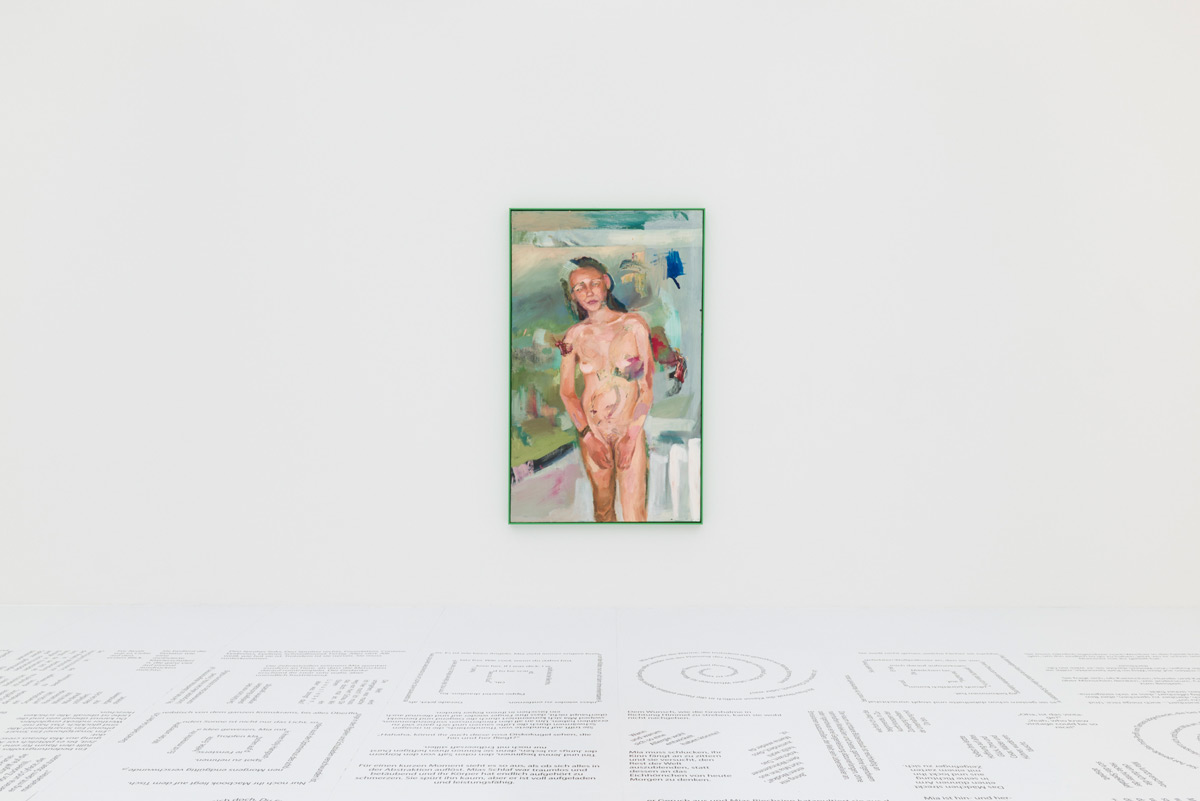

Seit Jahren reflektiert Iskin diesen Zustand zwischen den Realitäten. Mit Ironie und scharfem Blick transformiert er die interreale Welt in seine Kunst. In Werther to go zeigt er, selbst Angehöriger der Generation Y, uns nicht nur einzelne Bilder oder Objekte, vielmehr führt er uns in eine artifizielle Herzkammer des Interrealismus, um uns emotional mit diesem zu verbinden. Wir stehen auf dem Text und die Romanfiguren blicken in den Raum wie aus Fenstern. Dieser Eindruck wir dadurch verstärkt, dass die Bilder gerahmt sind. Es scheint, als stünden die Figuren zwischen unserer Welt, die wir als wirklich erfahren, und einer weiteren Welt jenseits des White Cube.

Die Ölportraits sind durch nicht-figurative Störungen verfremdet. Es scheint, als dringe eine jenseitige zweite Realität durch die Bilder zu uns hinein. Und so betrachten wir in Werther to go keine Mischwesen wie noch in Bastard Club, sondern gleichsam durch Fenster in eine andere Welt. Gleichzeitig hat man den Eindruck, sich in einem Panopticon zu befinden, jener Gefängnisform, in welcher die Insassen jederzeit beobachtet werden können, diesmal allerdings mit vertauschten Plätzen. Bei den BesucherInnen stellt sich das Gefühl ein, der Beobachtung durch die Romanfiguren nicht entgehen zu können. Auch scheint nicht ganz sicher, ob sich in den Bildräumen hinter den Portraits nicht noch weitere Personen befinden.

Iskin blickt kritisch auf das Leben in der Interrealität und die digitale Beschleunigung und Kommerzialisierung. Dies erkennt man an seiner Kunst, die immer ohne erhobenen Zeigefinger auskommt. Aus dieser skeptischen Haltung heraus könnte Iskin den Umstand, dass Menschen im Netz manipuliert werden, in Echokammern gefangen, und die damit verbundenen Gefahren, ebenso beschreiben wie einst Werther vor fast 250 Jahren seine Zeitgenossen: „Sieh den Menschen an in seiner Eingeschränktheit, wie Eindrücke auf ihn wirken, Ideen sich bei ihm festsetzen, bis endlich eine wachsende Leidenschaft ihn aller ruhigen Sinneskraft beraubt und ihn zu Grunde richtet.“

Werther to go, Titel der Ausstellung und des Romans. To go. Das To-Go ein Hin- und Her-Gehen zwischen den Welten? Die Abwesenheit von Ruhe und Stillstand. Die ewige Beschleunigung. Oder auch die Aufforderung, endlich zu gehen, sich all dem zu entziehen? Ein Gang zurück in die Realität. Vielleicht ist Iskin mit seiner Analyse des Interrealismus kein Träumer, sondern ein Realist.

Alexander Iskin lebt in Berlin, derzeit arbeitet er mit einem Stipendium der Pollock-Krasner Foundation in New York.

Werther to go

In his first exhibition at SEXAUER in 2014, titled Bastard Club, Alexander Iskin showed oil paintings of disturbingly comic mixed creatures in apocalyptic landscapes. Two years later, Iskin was no longer just mixing beings, but realities. In his exhibition Reality Express, he explored how analog and virtual reality interact in paintings. Interrealism was born. Since then, Iskin has been developing and exploring interrealism as an artistic practice, aesthetic, and media critique. In 2020 the Mönchehaus Museum exhibited Iskins first institutional solo exhibition, enabling interrealism to enter the museum.

After half a decade of exploring interreality through painting, installation, film, and performance, Iskin now presents an interrealistic novel, which will be published in 2022. Werther to Go. This text literally serves as a base for the exhibition. Iskin placed hundreds of printed quotations from the novel against a white background on the floor of the exhibition hall. As visitors walk through the hall, they experience a white cube in an ideal and hermetic space and they read or unconsciously absorb fragments of the text.

In his novel Werther to go, Iskin describes how the digital worlds effect the Generation Z, the cohort of post-millennials who no longer know a world without the Internet. Through digital manipulation, young people are exposed to extreme commercialization and other forms of manipulation. While fragmented texts from the novel cover the floor, Iskins paintings of the main characters hang on the walls. Thus, inside the cube, we encounter the artistic transformation of Generation Z.

In the novel by Iskin on which the exhibition is based, a professional hacker employed by a software company falls in love with a young girl whom he knows exclusively from a social network. The rather nature-loving and reserved girl is new to the big city. She has problems with her classmates, who are considered cool, seeks help on the Internet platform gutefrage.net and reads Goethe’s epistolary novel Die Leiden des jungen Werther (The sorrows of the young Werther). Using artificial intelligence that imitates Werther’s language, the professional hacker tries to manipulate the girl incognito on the platform. However, the girl proves to be resistant. In the end, the hacker tries to control the young girl, not only in the digital world but in the real world as well.

Of course, it is no coincidence that the protagonist reads Die Leiden des jungen Werther in Iskin’s novel. At that time, Werther was understood to stand against to an Enlightenment that was perceived as cold and rationalistic. For the young girl in Werther to go, Werther is also an emotional counter-project to the coldness of the digital: feeling instead of commercialization, truthfulness instead of simulation, nature instead of McDonalds. On the other hand – and this is the paradox – Goethe’s Werther influenced young people at that time just as strongly as digital media do today. After the novel’s publication in 1774, suicidal imitations, known as the Werther effect, occurred. Not unlike this, over two hundred years later, young people discuss their suicidal attempts on social forums.

In contrast to the Werther era, adolescents today are no longer influenced by reading an exceptional book, but spend part of their lives in a parallel world of digital reality. Quite a few are addicted to it. They are rarely in the “real” world in its entirety, but almost always with at least one eye in the virtual one. Trapped in interreality. Apparently voluntarily. Actually manipulated.

Iskin has been reflecting on this state between realities for years. With irony and a sharp eye, he transforms the interreal world into his art. In Werther to go, he, himself a member of Generation Y, does not just show us individual images or objects, rather he takes us into an artificial heart chamber of interrealism to connect us emotionally with it. We stand on the text and the characters of the novel look into the exhibition hall if they were trapped behind pop-up windows. This impression is reinforced by the fact that the paintings are framed. It seems as if the characters stand between our world, which we experience as real, and another world beyond the white cube.

The portraits are alienated by non-figurative interferences. It seems as if an otherworldly second reality intrudes on us through the images. And so, in Werther to go, we are not looking at mixed beings as we were in Bastard Club, but rather through pop-up windows connecting parallel worlds. One has the impression of being in a panopticon, that form of prison in which the inmates can be observed at any time, but this time with the places reversed. The visitors have the feeling that they cannot escape being observed by the characters in the novel. Nor does it seem entirely certain that there are not other beings in the pictorial spaces behind the portraits.

Iskin has a critical view towards the digital acceleration and commercialization of Interreality. This can be seen in his art, which always communicates without being directly offensive. From this skeptical position, Iskin could describe the fact that people are manipulated on the Net, trapped in echo chambers, and the associated dangers, just as Werther once described his contemporaries almost 250 years ago: “Observe a man in his natural, isolated condition; consider how ideas work, and how impressions fasten on him, till at length a violent passion seizes him, destroying all his powers of calm reflection, and utterly ruining him.”

Werther to go, title of the exhibition and the novel. To go. The to-go a going back and forth between worlds? The absence of rest and standstill. The eternal acceleration. Or also the invitation to finally go, to escape all that? A walk back to physical reality. Perhaps with his analysis of interrealism, Iskin is not a dreamer, but a realist.

Alexander Iskin lives in Berlin, and is currently working in New York on a project for the Pollock-Krasner Foundation.